Alexander Weheliye’s theorization of sonic Afro-modernity invites scholars in the humanities and social sciences to rethink how history, subjectivity, and modernity are apprehended. His intervention begins from a simple but far-reaching premise: certain texts exceed their linguistic textuality. When approached through what Weheliye calls “thinking sound,” these works disclose temporalities and modes of being that remain inaccessible through conventional literary or historical reading practices.

In Phonographies, Weheliye applies this method to canonical works such as W. E. B. Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk and Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, not to reinterpret them as aesthetic artifacts alone, but to interrogate how sound reorganizes history itself. Against linear, progressive, and totalizing narratives of time, Weheliye demonstrates how sonic forms open up alternative historical consciousness—forms that register Black subjectivity as multiply temporal and constitutively modern.

Sonic Temporalities and the Limits of Linear History

Ellison’s Invisible Man provides a crucial entry point into this argument. A conventional reading treats the novel’s engagement with history as narrative progression. That is, an accumulation of experience moving forward along a rigid timeline. Weheliye, however, draws attention to the novel’s sonic dimensions, revealing a tension between imposed historical linearity and lived temporal dissonance.

Ellison’s protagonist initially understands history as a closed trajectory: one must conform to its dictates or risk obliteration. He is invested in keeping Black life aligned with this timeline, mistaking participation for agency. It is only when Tod Clifton is killed—effectively erased from this historical schema—that the violence of this conception becomes unmistakable. Clifton’s death exposes a brutal truth: the timeline in question is not neutral. It is a racialized history in which the police function simultaneously as judge, witness, and executioner.

Weheliye’s intervention lies in redirecting our attention to the sonic environment surrounding this moment. By asking whose history Clifton has “fallen out of,” Weheliye destabilizes the authority of the linear, graph-based conception of history. Both Clifton and the protagonist emerge as dominated subjects precisely because their historical imagination remains captive to a framework that denies them authorship. As Weheliye observes, the appearance of a “sonic aperture” radically alters the conditions under which history can be perceived and inhabited.

Sound, in this formulation, does not merely supplement meaning; it transforms historical understanding itself. History is no longer conceived as the recovery of a fixed past or the management of a precarious present. Instead, sonic history unfolds as resonance, interruption, repetition, and improvisation. These are forms that resist closure and demand attentiveness rather than mastery.

Du Bois and the Phonographic Imagination

This sonic reconceptualization of history finds its most generative articulation in Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk. Du Bois was acutely aware of how dominant philosophies of history, particularly those derived from European thought, measured humanity through literacy and inscription. Thinkers such as Hegel notoriously dismissed Black peoples as ahistorical precisely because their intellectual traditions were not anchored in writing.

Souls can be read as a direct refusal of this logic. Du Bois does not simply write a book; he produces a work that disrupts genre boundaries and reorients historical consciousness itself. By embedding Negro spirituals within the text, Du Bois creates a work that functions less like a conventional literary artifact and more like a sonic recording—a phonographic inscription of Black life. Weheliye’s insight here is crucial. Although print technology predates the phonograph, it is the latter that provides the conceptual framework needed to grasp what Du Bois achieves. The spirituals do not illustrate the text; they punctuate it, pause it, and sonically thicken its meaning. They render Black interiority audible.

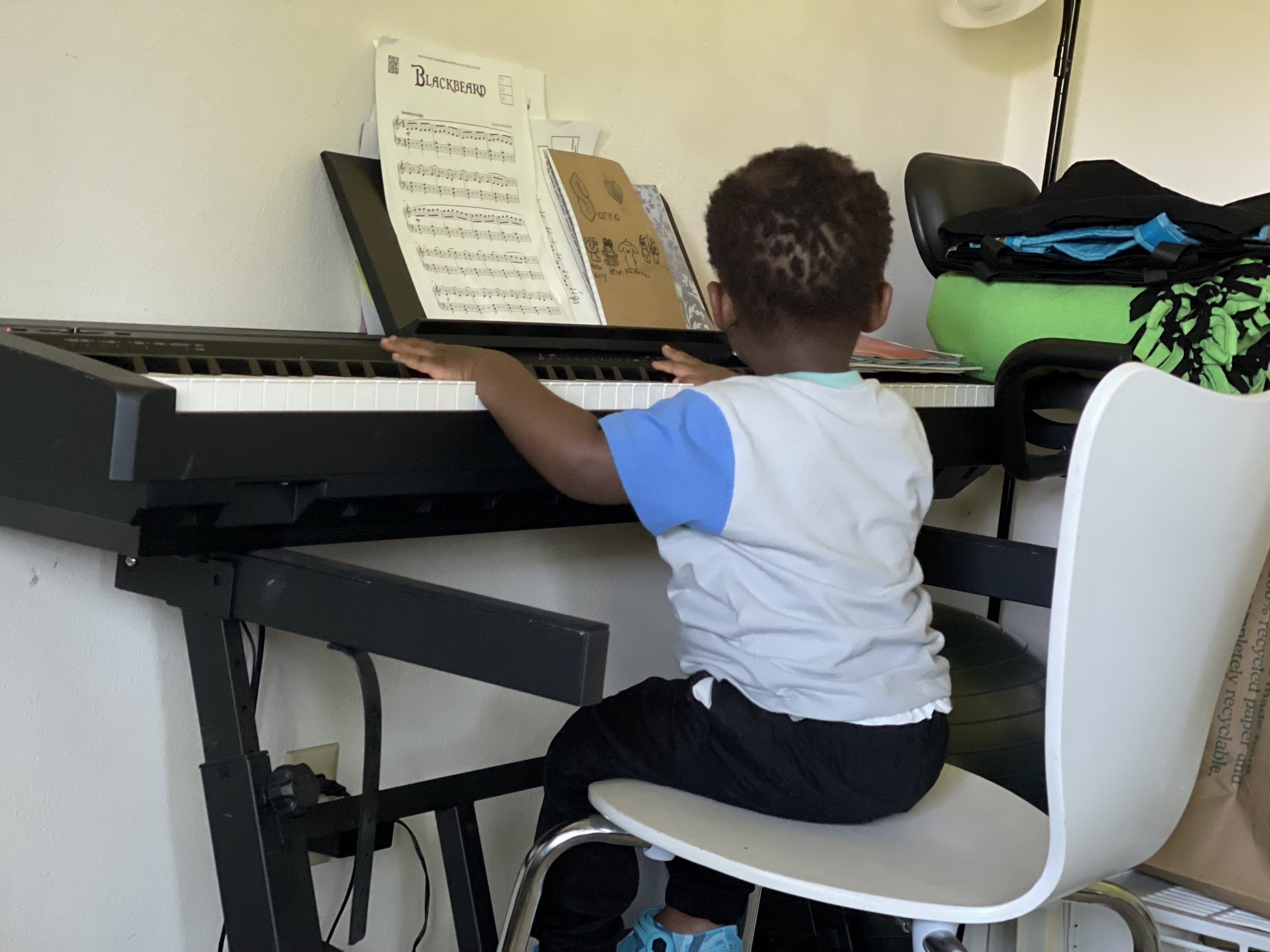

The sacred status of these spirituals within Black diasporic memory cannot be overstated. As the preacher and musician Phipps Wintley has observed, their emergence from the “black keys” of the piano serves as a powerful metaphor for Black subjectivity, one forged under conditions of captivity yet irreducible to suffering alone. As Weheliye argues, Du Bois’s privileging of sound inaugurates music as a primary channel for articulating Black subjectivity, temporality, spatiality, and culture throughout the twentieth century. In this sense, Souls functions as one of the foundational grooves of sonic Afro-modernity. Its theorization of double consciousness is inseparable from its formal innovation: the insertion of musical bars that interrupt the textual machine, forcing readers to listen as well as read. Sound becomes not an embellishment, but a structural principle of Black modern thought.

Consuming Sonic Technologies, Producing Subjectivity

Weheliye extends this analysis of sound into the realm of modern technology and everyday life. In his discussion of sonic technologies, he notes how modernity has unsettled traditional distinctions between public and private, sound and noise, urban and rural. These categories no longer possess stable meanings, as they are negotiated through taste, access, and power. Through Ellison’s essay “Living with Music” and Darnell Martin’s film I Like It Like That, Weheliye illustrates how sonic technologies allow individuals to traverse—and temporarily redraw—the boundaries of space. Music becomes a tool for constructing private worlds within public environments, a shield against unwanted social proximity.

Yet these sonic practices are not purely acts of resistance or autonomy. While listeners may appear to exercise agency by curating their auditory spaces, they are simultaneously shaped by the technologies and soundscapes they inhabit. The spaces they construct act upon them, producing new forms of subjectivity. This double movement—consuming sound while being consumed by sonic environments—captures something essential about modern Black life. Even when sonic spaces emerge from reactionary impulses, such as the desire to block out noise, they nonetheless generate new modes of being. Sonic technologies thus function not merely as tools, but as mediators of personhood in late modernity.

What ultimately emerges from Weheliye’s work is a methodological provocation. To think Afro-modernity adequately requires more than reading texts; it demands listening to them. Sound disorganizes inherited timelines, unsettles disciplinary boundaries, and foregrounds forms of Black life that exceed inscription. In attending to sonic Afro-modernity, we are compelled to rethink history not as a line to be followed, but as a field of vibrations—interruptive, recursive, and alive. Listening, in this sense, becomes both an ethical and intellectual practice, one attuned to forms of Black modernity that have always been present, even when dominant histories refused to hear them.