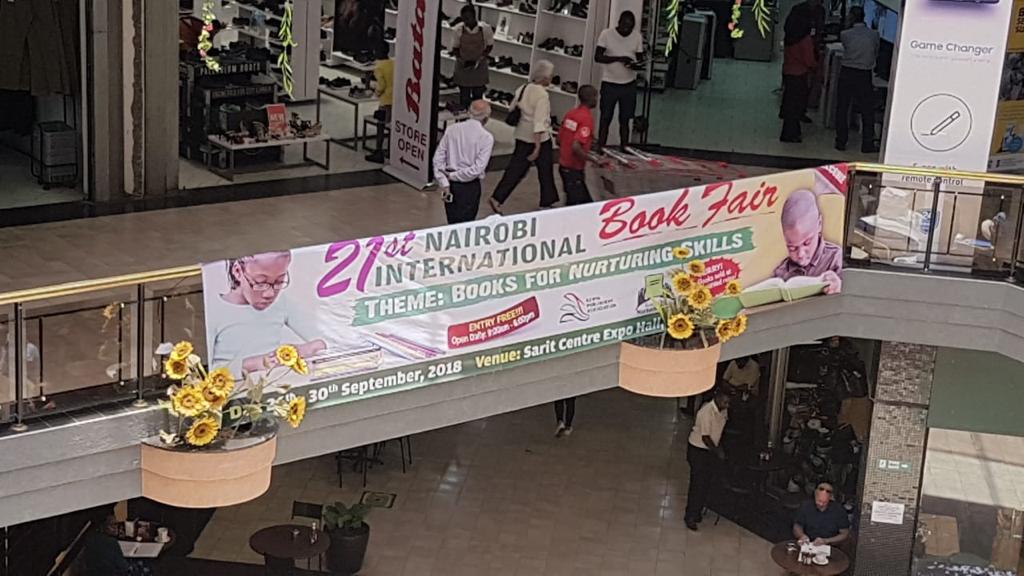

The just-concluded 21st Nairobi International Book Fair allows us to reflect on the trends in book publishing in Africa. In a way, international book fairs are a microcosm of the state of publishing in the continent. At the Nairobi International Book Fair, many publishers showcased school textbooks and a few creative or trade books. Save for a few university presses that had tertiary books, it appears that local publishers are not keen on producing knowledge for higher education or for general reading.

In the early 1990s, Philip Altbach argued in his essay, Perspectives on Publishing in Africa, that books were fundamentally significant to the development of African countries. Altbach pointed out that developing local publishing houses will allow African countries to not only create an infrastructure for intellectual culture but also resolve the challenge of sustaining an intellectual life with returns from sharing ideas. His argument underscores the fact that publishing is perhaps the best platform for creating a livelihood for the many Africans who work with ideas.

Altbach wrote his essay in the wake of multiparty democracy campaigns in most of Sub-saharan Africa. He envisioned that in the absence of credible media houses and constant government censorship, publishing houses were well suited to upholding free expression.

Though Altbach was cognizant of the neoliberal forces that privileged international publishing houses to the local ones, he was optimistic that African countries could still build and develop their own knowledge production infrastructure. In addition to South Africa, which had a thriving publishing industry, he singled out Kenya, Nigeria, and Zimbabwe as countries that had made significant progress in developing local publishing industries. He further observed that Tanzania, Ghana, Senegal, and Cote d’Ivoire could build a thriving publishing culture.

Although there are some research and a lot of policy reports that explore ways of developing new reading publics in Africa, most of these studies are either written from a neoliberal perspective that privileges books as commercial entities and authors as self-entrepreneurs or from a western perspective of knowledge production. While there is nothing wrong with publishers getting returns on their investments or authors earning a livelihood from their works, it is troubling when publishers limit themselves to producing school textbooks for basic education because they are more likely to be bought by parents or governments.

In my view, publishers who rely on government tenders undermine their ability to shape a reading public. Instead of producing books that engage society and issues that affect it, these publishers wonder in corridors of hotel conferences conducting workshops on how to write for governments. They are forever chasing government tenders and have no time to innovate or shape the educational agenda. Of course, there is nothing wrong with the act of gaining government tenders, after all, are governments not the major funders of basic education in most African countries? What is wrong are the models of publishing that are specifically geared in meeting government book demand.

If publishing houses are to develop into meaningful knowledge producing platforms, they must redefine their business models. They need to think beyond producing for basic education because most research is conducted at the university level. Since it is already established that few governments are keen on promoting local publishing industries beyond buying textbooks, publishers must devise ways of getting ahead of governments in shaping the reading public. Investments made in tertiary, trade books, and creative books publishing while may seem unprofitable in the short-term, have the potential of shaping the public psyche and developing new reading publics in the long-term, a situation that would be both beneficial to the business interests of publishers and authors, and the development of a nation.

Most publishers are quick to complain that the public does not read books, and therefore, they cannot waste their resources publishing books that will never sell. However, the reality is that many readers face challenges accessing books from the continent because of poor distribution. Many publishers are stuck with orthodox means of publishing that do not match the reading habits of the modern world. Whereas most of the world is doubling their efforts to have books on multiple platforms, most publishers in Africa restrict themselves to print publishing. It appears then that what is mostly construed as a lack of market for books can be addressed by developing better distribution channels.

In most African countries, publishing industries enjoy low entry requirement and have the privilege of autonomy and lack of constant government interference or regulation. This is the kind of freedom that enables innovation and allows creativity to flourish. It then seems to me that there are many opportunities for publishers to build the much-needed infrastructure for knowledge production in Africa. But if publishers participate in promoting neoliberalism, they risk being its first casualty.