Two years ago, Kenyan authorities arrested a Chinese restaurant owner who allegedly had a “no African” policy in his restaurant. The restaurant, simply known as Chinese Restaurant, is located in Kilimani, an affluent suburb for the upper class in Nairobi. Local newspapers reported that the restaurant only allowed tax drivers or Africans accompanied by Chinese, European or Indian patrons. Most Kenyans were outraged by these reports; they took into social media calling for the deportation of the Chinese business owners. The government was at first reluctant to act but they finally gave in to public pressure and arrested the restaurant owner for running a business without a license – but not for racism as most Kenyans would have preferred.

The restaurant cited security concerns as a reason why they barred Africans into the restaurant but this does not hold considering that they even barred prominent Kenyans, a former cabinet secretary, and a permanent secretary who would not by any chance be members of Al-Shabaab, the militant Somali based terrorists that the Chinese patrons were afraid of. Even if the threat was plausible, it is not a viable reason for profiling people and singling out a race as potential terrorists. Most Africans considered the actions of the Chinese patrons as racist but there is no way of knowing their true motive. It could be that they were truly concerned about their safety or they did not simply consider Africans worthy of their company. I have considered this question carefully, and I contend that what happened in Nairobi was a matter of misguided cultural power dynamics between Africans and Chinese patrons.

Most Chinese in Kenya have no previous experience with the various ethnic groups that make up the country. Even though Chinese contact with Kenyans dates back to Sung Dynasty (960-1279), it’s only recently that their presence in Kenya has become noticeable. There is archeological evidence of Chinese presence in the Kenyan coastal region, particularly in Lamu. Local legend has it that 20 shipwrecked Chinese sailors washed up on the shore hundreds of years ago, and the locals rescued them. The sailors converted to Islam, intermarried with Africans, and were assimilated into the community. A report on China Daily, July 11, 2005 indicated that DNA tests conducted on Kenyan women in Lamu confirmed that they were of Chinese descent. This indicates that Africans and Chinese have had a cordial encounter and are not incapable of living together. However, the recent wave of Chinese migration into Africa while beneficial economically, it poses new type of cultural challenges.

China established diplomatic relationship with Kenya in December 14, 1963, shortly after Kenya’s independence. Despite the two country’s different economic models – Kenya having embraced capitalism while China favored communism – they have continued to enjoy a cordial relationship. According to the University of Nairobi’s Institute for Development Studies’ 2008 report on China-Africa Economic Relations, The Chinese embassy in Kenya is arguably their largest embassy in Africa both in terms of size and employees. This may perhaps explain the surge in Chinese immigrants to Kenya in the last two decades. The Chinese contractors are managing major government and private constructions across the country.

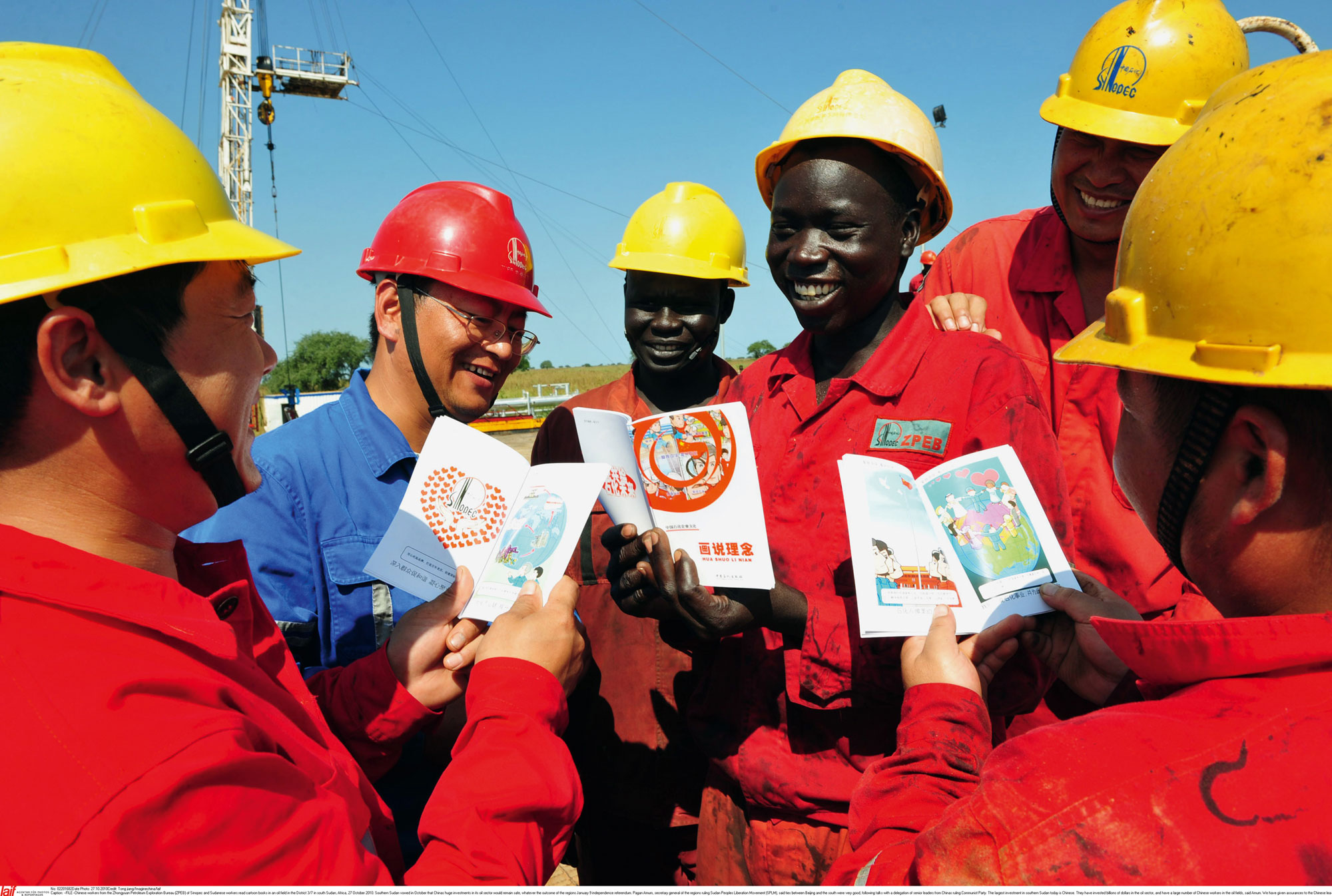

Despite the thriving construction industry, the major Chinese immigrants are mostly merchants, importing merchandise and selling to retailers in Kenya. I have observed that Chinese traders in Kenya rarely deal with the locals directly; they prefer working with middlemen, thus avoiding the necessary contact that can boost their familiarity with the host. Furthermore, the Chinese construction companies do not hire Kenyans; they do all the work and sometimes prefer living in their own quarters. With this kind of lifestyle, the Chinese have little exposure with local people, and have no way of learning about local culture, leave alone embracing it.

Interestingly, due to Chinese investment in Kenya, some Kenyans are learning Mandarin through the Chinese sponsored Confucius Institutes around the country. However, one cannot stop to think that the cultural literacy is only happening one way, hence creating a cultural power dynamics. Howard French’s 2014 book, China’s Second Continent: How a Million Migrants are Building a New empire in Africa, has extensively covered this aspect of cultural power dynamics between ordinary Chinese investors and Africans. French writes a story about a Mr. Hao Shengli, an investor in Mozambique whose belief about Africans is in the lines of “I didn’t think they were so clever, not so intelligent…we had to find backward countries, poor countries that we can lead, places where we can do business, where we can manage things successfully” Obviously Mr. Hao does not hold Africans in high esteem. To him African culture is subservient to his.

As much as Mr. Hao is not a representative of Chinese people, in a way he is typical of most investors who now flock various cities across Africa. Most countries in Africa have yet to reflect on the impact of Chinese investment in their countries. But with the increasing immigration of Chinese businesspeople into African cities, this kind of reflection is inevitable. As often is the case, the most noticeable effects are on cultural compatibility. The Nairobi incident demonstrates that there is a wide cultural divide between Africans and Chinese. This issue must be addressed with utmost urgency lest the cordial relationship China enjoys with African countries be ruined.

Of course it is upon the Chinese businesspersons to learn the African philosophy of Ubuntu (humanness), and African Values of community. There is a lot to be gained through mutual respect and honest dealing. As much as the Chinese government is investing in Africans who are trying to learn Chinese culture, it should do the same to the Chinese who want to learn African cultures. For China to represent a new awakening, it must do, and behave better than the European colonizers at whose hands Africans were humiliated and their dignity violated.

The incident in Nairobi, for all we know, may have been a misunderstanding but nevertheless it sowed seeds of discord and loss of trust that the Kenyans had for Chinese business-people. Deliberate steps must be taken to restore the relationship to its better form. It seems to me that cultural knowledge may be the most important business skill that any Chinese hoping to invest in Kenya or Africa ought to possess. History shows that most Asians who have come to Africa for whatever reason usually prefers to build a home in their host countries. The Indians who built the railway in East Africa are now part of our proud heritage. Even though most of them never made any effort to integrate or assimilate to the local culture, they somehow found ways of maintaining a healthy relationship with Africans. There are a few exceptions to this, for instance, the tragedy that came with Dictator Idi Amin of Uganda who in the 70s expelled Asians from Uganda. The Ugandans saw the Asians as a threat to their economic lives. Of course they were wrong but populist ideas and reasoning often do not go together.

There is no better way of securing the future of Africans and the Chinese than to invest in cultural programs that foster mutual respect. Such programs might include student, farmers, businesspeople, and government exchange programs among others. Of course, such programs often take long in impacting a society. But they are worthy looking into.