by Vincent Ogoti | May 3, 2020

This essay discusses the impact of digital technology on education. It focuses on blended learning as a product of computer-mediated environments that allow learners and teachers to create a learning environment that combines the advantages of online technologies and face-to-face methods of learning. The essay demonstrates that the dichotomy between the digital natives and digital immigrants do not apply in blended learning as the approach does not seek to replace the conventional brick-and-mortar classroom or constrain itself to online learning

Significant studies about the so-called digital natives, a

population of students growing up in contexts with broad access to

communication technologies (Prensky, 2001; Bennett, Maton, & Kervin, 2008),

focus on how the traditional educational system fails to meet the learning

needs of these students (Margaryan, Littlejohn, &Vojt, 2011). Other studies

examine the extent to which these students integrate digital technologies in

their studies (Ferdousi and Bari 2015), or the adverse effect of technology on

digital natives (Hawi & Samaha, 2016; Kirschner & De Bruyckere, 2017)),

or contests the existence of digital natives (Bennet et al., 2008; Jones &

Healing, 2010). While this scholarship teases out the primary debates on the fundamental

significance of technology to student learning, they often neglect discussions

regarding the critical role of instructors in developing lessons that appeal to

students born into computer-mediated environments. There are fewer studies that

delve into the practical aspects of designing lessons in a computer-mediated

environment. The ones that do often relegate teachers born before the 1980s into

a category Jones and Healing (2010) refer to as digital immigrants: teachers

born before the rise of digital technology. While this essay concurs with

Bennet et al., (2008) and Jones & Healing (2010) that the binary between

the so-called digital natives and digital immigrants is unstable and

undertheorized because scholars often base their claims on limited empirical

evidence, it argues that blended learning addresses the challenges of combining

traditional face-to-face learning environments with digital technology.

Blended learning is a system of restructuring the classroom

experience through designing lessons that coalesces the strengths of both

face-to-face instruction techniques and online learning into a blended and more

effective learning experience (Garrison and Vaughan 2010). The idea of “system”

shows that the effectiveness of blended learning lies in harnessing the

advantages of face-to-face classroom contact hours and the benefits of

asynchronous online communication (Graham, 2005). However, as Randy and Heather

(2004) cautions, blended learning does not refer to an enhanced

brick-and-mortar classroom that uses technology to supplement its learning

activities. It instead underscores the coalescing of two different environments

into a unique learning experience that rethinks traditional teaching and

learning. The concept of blended learning gained tract in the early 1990s when

the personal computer became a household device to many families in developed

countries. The concept has evolved with the advancement of technology, which

allows many people to access the internet through mobile devices and computers.

Blended learning has moved beyond educational institutions to the business

world, where training and workshops run as blended learning activities.

However, this essay will focus on blended learning in the academic context.

A blended learning environment allows instructors to design

lessons that maximize different forms of learner interaction, such as directly

with the teacher, with other students, and with the content or teaching

material. Learners cannot achieve these forms of interactions in an exclusive

online or onsite learning environment. Graham (2014) argues that blended

learning lessons provide a platform for achieving these interactions because it

focuses on learner affective and cognitive engagement. He bemoans the practice

of designing lessons that only engage the learner’s mind (cognitive), and notes

that student interactions that often lead to a successful learning experience

go beyond the mind into the learner’s heart (affective). For instance, the

motivation to learn a new language is not innate to all students. Therefore,

instructors should cultivate it through creative onsite and online activities

that light up the students’ “passion, desire, and confidence for learning”

(76). The effectiveness of this technique rests on the idea that while

face-to-face learning environment allows educators to create spontaneous

interactions with students, it constrains their ability to attend to the

individual needs of all students (especially in large classes) in the time

allotted for a lesson. However, through online interaction, which is not

limited by time and place, an instructor can tailor learning activities to

individual learners and groups. Thus, blended learning transcends the

constraints of online and brick-and-mortar classrooms by combining the

strengths of both onsite and online environments to create an efficient,

effective, and engaging learning experience.

Technology enables teachers to create a blended learning environment that encourages an in-depth approach to learning, improving student attention, and engagement. Garrison and Vaughan (2008) elaborate on this learning approach as “an intention to comprehend and understand the meaning and significance of the subject at hand” (43). The central feature of this approach is that the conditions we create in a learning environment shape how students engage in a lesson. To most students, particularly in the West, the line between face-to-face and online experiences is thin, as they seem to move seamlessly between these worlds. However, this does not mean that these students are always open and willing to form a learning community in these environments, nor does it imply a sense of homogeneity among these students, as Prensky (2002) does. Therefore, both instructors and students work together to nurture open communication that will make learning communities possible. They can attain this goal through designing blended learning lessons that move beyond the quality of learning outcome and instead incorporate informal practices that allow personal relationships to develop organically. For instance, creating online “chat” forums can allow learners to interact informally and ease the tension that often discourages students (especially those at different levels of learning) from collaborating or even contributing to discussions during a face-to-face lesson.

Blended learning enables instructors to find a balance between

face-to-face learning and online learning that supports learner immediacy and

social presence. Jared et al., (2011) describes learner immediacy as

communication behavior that improves closeness between or among communicants. Social

presence is the ability of learners to present themselves as “real people” with

feelings. In a face-to-face learning environment, both learners and instructors

keep a high level of fidelity or authenticity because they share the same

brick-and-mortar space. In an online environment, interactions have low levels

of fidelity due to lack of immediacy. However, the difference in time and space

allows the online environment to be more flexible compared to a face-to-face

environment. The challenge lies in blending these two modes of learning without

compromising instructor and learner immediacy and social presence. Jared et

al., (2011) discusses how combining platforms such as Facebook video messaging,

VoiceThread video commenting, and video blogs can enhance learner immediacy and

social presence. Technology allows institutions to design sophisticated

learning management systems, such as Canvas, that incorporates social media

capabilities with customized tools for enhancing learner immediacy. Furthermore,

a learning management system can potentially mitigate privacy challenges, which

are typical in social media platforms. Ferdousi and Bari (2015) argue that

technology enhances undergraduate education because digital natives are

predisposed to computer-mediated environments. I contend that these technology

tools are user-friendly and do not require advanced digital literacy.

Therefore, instructors can learn how to combine various media platforms with

learning management systems to create a desired blended learning environment.

Audio-visual technology constitutes the primary tools for

blended learning, and recent advances in these technologies allow teachers to

tailor, edit, or adopt sounds and videos for a blended lesson. Despite this,

research on the use of audio-visual technologies in blended learning does not

show the extent of their usefulness. There is little empirical data that

outlines how instructors and students should determine the relevance of

audio-visual technologies (Canning, 2000). The use of these technologies evokes

challenges such as determining how much exposure to a video can enhance student

learning, how auditory components should enhance visual component, how many

times students should play the video, and how to integrate an online video task

with classroom instruction. Canning’s (2000) research, although conducted two

decades ago and in the context of language learning, outlines elements that are

still relevant in blended learning. She encourages instructors to limit videos

to about four minutes because students get distracted around this minute mark. Canning

further notes that getting the right length does not mean students will engage

the videos effectively. Therefore, instructors should design meaningful and

challenging tasks that motivate learners to engage with the video. Recent

scholarship, particularly by Brame (2017), gives additional elements for

designing useful videos for blended learning. They include aspects that deal

with cognitive reasoning (such as signaling critical points in a video, segmenting

content, and using conversational language), and active learning. It appears

then that audio-visual technology can be harnessed and effectively utilized for

blended learning.

While blended learning is a product of advances in computer

technologies, which have become more accessible in the last few decades, we

cannot constrain it to the category of digital natives. Blended learning

reveals that technology is yet to replace traditional modes of learning.

Instead, technology has enabled instructors to combine conventional learning

methods with online techniques to develop a blended learning classroom that

takes advantage of the strengths of these two environments. Therefore, in

blended learning, the dichotomy between the so-called digital natives and

digital immigrants does not apply. Future research should focus on examining

the scope of blended learning to find out whether it can be used in all

subjects.

References

Bennett, S.,

Maton, K., & Kervin, L. (2008). The ‘digital natives’ debate: A critical

review of the evidence. British Journal of Educational Technology, 39(5),

775-786.

Brame, C. J. (2016). Effective Educational Videos:

Principles and Guidelines for Maximizing Student Learning from Video Content. CBE—Life

Sciences Education, 15(4), es6.

https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.16-03-0125.

Canning, C. (2000). Practical Aspects of Using Video in

the Foreign Language Classroom, The

Internet TESL Journal, 6(11). https://iteslj.org/Articles/Canning-Video.

Ferdousi, B., & Bari, J. (2015). Infusing

mobile technology into undergraduate courses for effective learning. Procedia-Social

and Behavioral Sciences, 176, 307-311.

Graham, C. (2005). “Definitions, Current Trends, and Future

Directions.” In Bonk Curtis, Graham Charles, and Cross Jay. The Handbook of

Blended Learning: Global Perspectives, Local Designs. (New York: Wiley).

Graham,

C.R. (2014). “Engaging learners in a Blended Course.” In Stein, J and Graham,

C.R (ed). Essentials for Blended

Learning: A Standards-Based Guide. (New York: Routledge).

Hawi, N. S.,

& Samaha, M. (2016). To excel or not to excel: Strong evidence on the

adverse effect of smartphone addiction on academic performance. Computers

& Education, 98, 81-89.

Jared

et.al., (2011). “The Use of Asynchronous Video Communication to Improve

Instructor Immediacy and Social Presence in a Blended Learning Environment.” In

Kitchenham, A (ed.). Blended Learning Across Disciplines: Models for

Implementation. (British Columbia: UBC).

Kirschner, P.

A., & De Bruyckere, P. (2017). The myths of the digital native and the

multi-tasker. Teaching and Teacher Education, 67,

135-142.

Margaryan, A.,

Littlejohn, A., & Vojt, G. (2011). Are digital natives a myth or reality?

University students’ use of digital technologies. Computers &

Education, 56, 429-440.

Prensky,

M. (2002). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants Part 1. On the Horizon. https://doi.org/10.1108/10748120110424816.

Randy, G. and Heather, K. (2004). Blended Learning:

Uncovering its transformative potential in higher education. Internet and

Higher Education, 7. 95-105.

Randy, G. and Norman, V. (2010). Blended Learning in

Higher Education: Frameworks, Principles, and Guidelines. (San Francisco:

Jossey-Bass).

by Vincent Ogoti | Nov 27, 2019

How does one tell stories of people whose lives bear scars and wounds of trauma and violence? Jonny Steinberg’s book, Little Liberia (2011), is a testament to the complexities of representing the life of the Other. Steinberg’s book shows the challenges of negotiating the self, the other, and disciplinary norms to craft a story that honors the wishes of the informant without compromising the ethos of scholarly work, which in the case of literary ethnography may include, inter alia, commitment to greater good, taking responsibility for the freedom and the well-being of the other, being open and transparent, and being cognizant of bias. Steinberg’s Little Liberia like his other works – Midlands (2002), The Number (2004), Three-Letter Plague (2008), and A Man of Good Hope (2015) – blends ethnography and biography to tell the stories of Jacob and Rufus whose lives are intertwined in many ways.

I chose Little Liberia for review because Steinberg’s works exemplify what it means to push the boundaries of disciplinary focus to craft narratives that straddle the lived experience of people while remaining anchored in the systematic way of producing knowledge. Steinberg traces Jacob and Rufus’ lives from the present-day streets of Staten Island in New York to Liberia, their country of origin, and back to New York. At the core of the story is the quest for relevance on the part of Rufus and Jacob. They are children of war; born into a tumultuous and chaotic country with a deeply entrenched system of structural violence that limits any form of personal development or fulfillment. They both fight this system, albeit differently. Rufus is the older of the two; a trained tailor with a passion for improving the lives of the youth in Liberia through soccer. Jacob was a student at a university who was keen on taking an active role in liberating his country from the warlords who were tearing it apart. They both fled the conflict, at different times, but ended up in Park Hill in Staten Island – a place where the majority of Liberian refugees in the United States have come to regard as the “Little Liberia.”

Steinberg follows these men as they go about their business of community building in Park Hill. They both work with a large community of Liberian immigrants living in Staten Island, particularly in Park Hill, which has become a microcosm of the country the refugees fled. Here, refugees reenact the very politics that led to their exile and homelessness. Steinberg quickly learns that Jacob and Rufus do not like each other. Even though they share a similar heritage, their trajectories are marred by controversy and back-biting as they compete for attention, influence, and grant money. Steinberg is not a stranger to these kinds of stories. He has remarked in several interviews that his works explore stories of people and communities in transition; that is, he investigates how political transition changes the filigrees of unwritten rules through which people come to understand themselves and the other.

In Little Liberia, Steinberg maps the landscape of Park Hill like a linguistics landscape ethnographer. For instance, as the story unfolds, he lets us into a long shot of the Park Hill neighborhood. The place was quiet. He comments, “perhaps I was on the streets of some abandoned utopia, that this place had once been crowded, but that nobody lived here anymore” (1). He then zooms in to let us see an “ABC Eyewitness News” pitch-black van parked on the side of the road, which lets us into the soundscape, “a disembodied voice, a reply, then another – a veritable commentary tossed from one window to the next.” For several pages, Steinberg does not let us see living bodies; he wants us to take in the landscape and understand its contours. Later in the story, I began to understand that Park Hill neighborhood is as much a character as is Jacob or Rufus. The landscape demands the same attention as do human characters. It is through its description and documentation that we begin to understand how Liberian refugees reenact their lives in the US. Steinberg unravels this landscape in ways that allow us to smell, see, hear, and experience the lives and of people in the neighborhood.

His extraordinary reflective practice draws us into his writing process. He places himself in the story and lets us know of his thoughts. Furthermore, he actively questions his conclusions and even engages his interlocutors to reach a better understanding. For instance, at one point while walking home with Jacob, he says:

I brooded over his (Jacob) last comment: Remember where you are from. The Kids in the room all had American accents and dressed like gang bangers in their low-slung pants, their exposed underwear, and their converse shoes.

‘Was every kid in that workshop African? I asked.

‘They were all Liberian.”

‘Why were there no-African-American there?

He said nothing, and we walked in silence for a long time.

Here, Steinberg honors silence. He wants to understand an issue, but his informant is not willing to diverge any information. He waits for another time to pose the question. This practice is an excellent lesson in literary ethnography – the ability to understand that often, informants do not have a language to articulate their story or even to answer your questions. Steinberg’s practice resists imposing his interpretation on silences. Instead, he waits patiently to reframe the question.

In addition to observation and interviews, Steinberg travels to Liberia to talk with people who knew Rufus and Jacob’s lives before they fled to the US. The visit allows him to present a well-developed story about his informants. It also allows him to ground his interpretation on much wider evidence. His earlier work as a journalist in South Africa plays a role here – he wants evidence, and he goes looking for it. Although this step does not seem necessary, especially if one acknowledges that the value of a literary ethnography does not lie in how well it represents the “objective truth,” it does serve a function in this particular story. Rufus and Jacob make claims about a violent conflict in Liberia that can potentially affect the lives of many families. Thus, it pays to countercheck their claims and the contradictions in their stories.

After spending a year and ten months shadowing Rufus and Jacob around New York, Steinberg completed his manuscript and gave copies to both Jacob and Rufus to comment, clarify, or contest any issue in the manuscript. He told Rufus, “if there are things you disagree with, not just matters of fact, but of perspective, about your fight with Jacob, about your vision for Rosa, about your trip to Monrovia, please share with me” (259). He lets us into his mind to peek on his reason for letting his informants shape the story he will finally publish. “My mind drifted, I felt anxious. I found myself wondering whether I could ever know much about this man’s experiences without being there, next to him, as they unfolded” (259). Here lies Steinberg’s gift as a literary ethnographer – the capacity to understand the limits of your craft. Ethnographers can learn a lot from his practice, that is, allowing the informant to challenge your conclusion and interpretation of their lives.

Later, Jacob called him to complain about problems in the manuscript. Problems that might affect families in the Park Hill neighborhood and even back home in Liberia. How did Steinberg address Jacob’s concerns? He reflects on the role of an ethnographer and the imagination of the informant. I share his reflections here to underscore the complexity of representing the life of the other and how ethnographers can exercise empathy without compromising their ‘agency to represent.’

Reading a book-length depiction of yourself for the first time is shocking, always, for everybody who has had the experience. You have spoken into a voice recorder for months, years. As you talked, you’re censored here and embellished there; you felt increasingly comfortable and in control; you were, in fact, writing a persona into the pages of the book that was still to be written. When you finally open the manuscript, you discover that you never were the one with the pen. The person, the writer, has contrived is recognizably you in detail. But in the spirit, something is awry. The writer has cheated. He has written a you that is not you: certainly not a you that you would care to present. You have given him material that you ought to have kept to yourself, that only you should have the right to clothe and display (260).

This quote underscores the major challenge of literary ethnography: the ethnographer takes the informant’s words (words that may have been carefully selected to build a specific persona), his interpretation of those words, and weaves a story of a persona the informant would rather keep hidden. Steinberg sat with Jacob and tried to understand his complaints. In the end, he managed to change a few passages in the story, but mostly let the story be. He remarks that while a writer of fiction is a master of his house with the freedom to do whatever he wishes; the writer of nonfiction is a renter who must obey the conditions of the lease. It seems then that a literary ethnographer – in this case, a writer who blends ethnography and biography to represent the other has the freedom to use the creative techniques of fiction but must always remember his duty to ethnographic truth (whatever that may be).

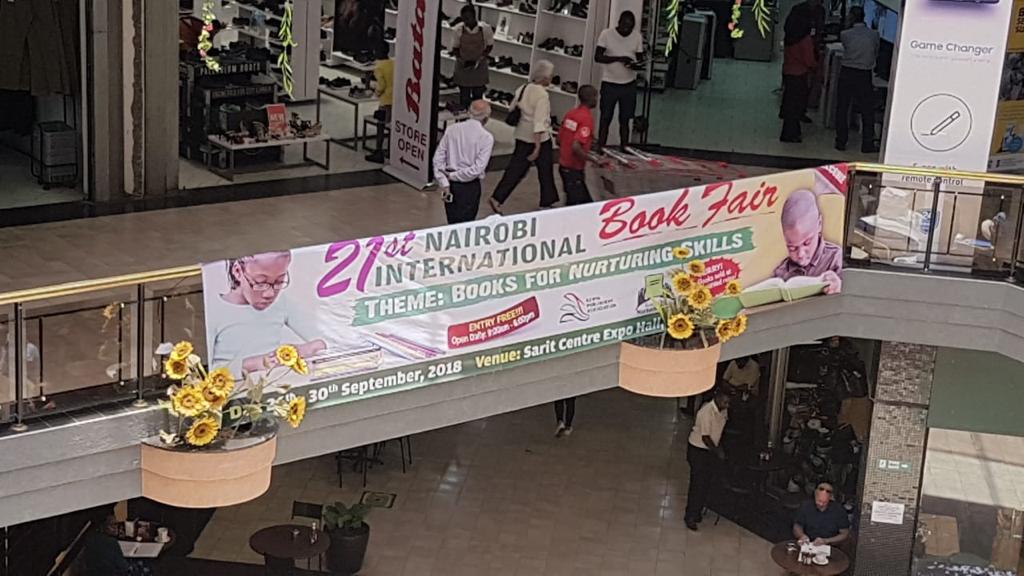

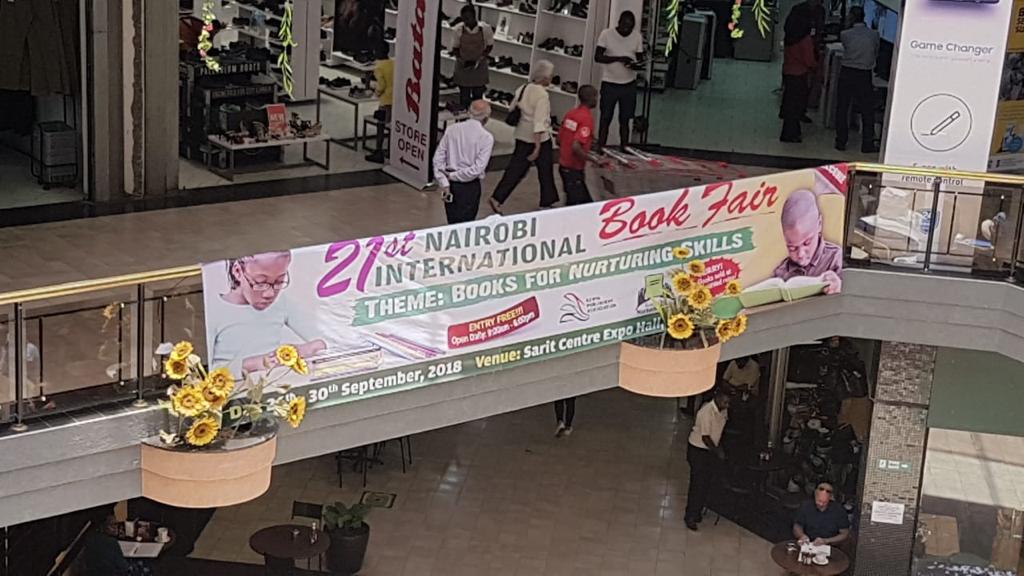

by Vincent Ogoti | Oct 18, 2018

The just-concluded 21st Nairobi International Book Fair allows us to reflect on the trends in book publishing in Africa. In a way, international book fairs are a microcosm of the state of publishing in the continent. At the Nairobi International Book Fair, many publishers showcased school textbooks and a few creative or trade books. Save for a few university presses that had tertiary books, it appears that local publishers are not keen on producing knowledge for higher education or for general reading.

In the early 1990s, Philip Altbach argued in his essay, Perspectives on Publishing in Africa, that books were fundamentally significant to the development of African countries. Altbach pointed out that developing local publishing houses will allow African countries to not only create an infrastructure for intellectual culture but also resolve the challenge of sustaining an intellectual life with returns from sharing ideas. His argument underscores the fact that publishing is perhaps the best platform for creating a livelihood for the many Africans who work with ideas.

Altbach wrote his essay in the wake of multiparty democracy campaigns in most of Sub-saharan Africa. He envisioned that in the absence of credible media houses and constant government censorship, publishing houses were well suited to upholding free expression.

Though Altbach was cognizant of the neoliberal forces that privileged international publishing houses to the local ones, he was optimistic that African countries could still build and develop their own knowledge production infrastructure. In addition to South Africa, which had a thriving publishing industry, he singled out Kenya, Nigeria, and Zimbabwe as countries that had made significant progress in developing local publishing industries. He further observed that Tanzania, Ghana, Senegal, and Cote d’Ivoire could build a thriving publishing culture.

Although there are some research and a lot of policy reports that explore ways of developing new reading publics in Africa, most of these studies are either written from a neoliberal perspective that privileges books as commercial entities and authors as self-entrepreneurs or from a western perspective of knowledge production. While there is nothing wrong with publishers getting returns on their investments or authors earning a livelihood from their works, it is troubling when publishers limit themselves to producing school textbooks for basic education because they are more likely to be bought by parents or governments.

In my view, publishers who rely on government tenders undermine their ability to shape a reading public. Instead of producing books that engage society and issues that affect it, these publishers wonder in corridors of hotel conferences conducting workshops on how to write for governments. They are forever chasing government tenders and have no time to innovate or shape the educational agenda. Of course, there is nothing wrong with the act of gaining government tenders, after all, are governments not the major funders of basic education in most African countries? What is wrong are the models of publishing that are specifically geared in meeting government book demand.

If publishing houses are to develop into meaningful knowledge producing platforms, they must redefine their business models. They need to think beyond producing for basic education because most research is conducted at the university level. Since it is already established that few governments are keen on promoting local publishing industries beyond buying textbooks, publishers must devise ways of getting ahead of governments in shaping the reading public. Investments made in tertiary, trade books, and creative books publishing while may seem unprofitable in the short-term, have the potential of shaping the public psyche and developing new reading publics in the long-term, a situation that would be both beneficial to the business interests of publishers and authors, and the development of a nation.

Most publishers are quick to complain that the public does not read books, and therefore, they cannot waste their resources publishing books that will never sell. However, the reality is that many readers face challenges accessing books from the continent because of poor distribution. Many publishers are stuck with orthodox means of publishing that do not match the reading habits of the modern world. Whereas most of the world is doubling their efforts to have books on multiple platforms, most publishers in Africa restrict themselves to print publishing. It appears then that what is mostly construed as a lack of market for books can be addressed by developing better distribution channels.

In most African countries, publishing industries enjoy low entry requirement and have the privilege of autonomy and lack of constant government interference or regulation. This is the kind of freedom that enables innovation and allows creativity to flourish. It then seems to me that there are many opportunities for publishers to build the much-needed infrastructure for knowledge production in Africa. But if publishers participate in promoting neoliberalism, they risk being its first casualty.

by Vincent Ogoti | Sep 24, 2018

Carol Cohn’s Women and War has challenged me to reflect on the following questions: With all the legislation and resolutions calling for a more participatory role for women in peacebuilding, how come peace negotiation tables or peace processes are dominated by men? Will peace agreements be effective if more women were involved? During the 2008 peace negotiations in Kenya, there was a 33% women representation in the mediation team and 25% representation at the negotiation table. The peace agreement signed resulted in a new constitution that gave a very critical treatment to gender. It rejected the historical exclusion of women from the mainstream society and struck at the socio-legal barriers that Kenyan women have faced over history. The new constitution created space for women to maneuver their way in the private and public sphere on an equal footing with men, but also institutionalized direct gender-specific measures that sought to correct the consequences of women’s historical exclusion from the society. Such measures included affirmative actions that sought to elevate women to a pedestal that had hitherto been the preserve of men.

Whether the women negotiators made all this possible is hard to tell, but we can clearly deduce that women did gain a lot from this new constitution. However, the implementation process was clearly designed in a way that involves both genders, that is, no state department or commission can be headed and deputized by people of the same gender. Has this solved the problem of gender imbalance in my country? No. Unfortunately, most agencies headed by women have been criticized in the recent past for underperforming. The public, which does not take into account the fact that the women who were appointed into the offices were either politicians or friends of politicians and that their performance does not in any way reflect the ability of women to hold higher offices, have already expressed their stereotypes that women cannot do certain jobs.

Some initiatives such as affirmative actions have backfired. For instance, when you lower university points for female students, you give them an opportunity to join university but force them to compete with male students for certain majors considered “good” e.g. Medicine, Law and Engineering etc., you haven’t improved their future as much.

I think the best way of involving women in peace processes is to go back to the basics. We first have to educate the society on the critical position a woman occupies. It is not enough that individual women know their rights, the whole society must be educated in this to the extent that they cease from making gender distinctions consciously or unconsciously. When this is done, people will remember to involve women in pre-negotiations, which mostly determines who gets a seat at the table, which in turn determines the affairs of a post-conflict society.